Nanaimo 49° 9' 49.96" N, 123° 56' 17.24" W Academia/Research Group

AboutEdit

In 1997 Dr. Imogene Lim received funding from BC Heritage Trust to research the history of Chinese Canadians in Nanaimo, British Columbia. The research began with the assistance of Colleen Stuart, who was then Dr. Lim’s student; she was hired as a researcher for the project. In addition, Qun Chen was employed as a translator for a number of the historic Chinese documents. Since then, others have been involved in making this project a success. They include Nancy Jones, Kelly Muir, Nathanael de Jager, and Brent Lee. Brent, in particular, is to be thanked for making the “bells and whistles” of this website actually work. Malaspina University-College continues to support this project as it evolves and develops.

Nanaimo's ChinatownsEdit

While few physical vestiges of Nanaimo's once thriving Chinese community remain, the story of Chinese settlement offers fascinating insight into one of Nanaimo's oldest, and the important economic and cultural role it played in the City’s development.

Origins of Chinese Settlement in NanaimoEdit

Gold rushes brought many Chinese to North America in the mid-1800s; first to the United States, then to Canada. But in Nanaimo, coal was the lure, especially during the winter months when cold weather in the Province's interior discouraged gold mining. Most of the Chinese who came to Nanaimo were from Guangdong Province (Canton delta region) and the four counties of Toi-san, Sun-wui, Hoi-ping, and Yin-pang.

Like other immigrants they followed the footsteps of countrymen or relatives seeking a better life. From the mid-1800s, population pressures, limited land opportunities, floods, famine and political instability caused many to leave despite the Chinese government’s prohibition against emigration.

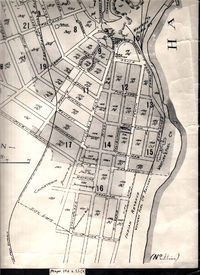

The First Chinatown (1860s - 1884)Edit

The first Chinese arrived in Nanaimo in the 1860s to work as labourers for the Vancouver Coal Mining and Land Company. They lived mainly in company-built structures in the Esplanade and Victoria Crescent area. Services to support the workforce soon followed, including a store opened by Mah Hong Jang in 1872 near Pioneer Square. By the mid-1880s Nanaimo’s Chinese community was the third largest in British Columbia, after Victoria and New Westminster.

The Second Chinatown (1884 - 1908)Edit

Chinese were perceived as unfair labour competition in the local mines, especially during times of high unemployment. This was a racist era and non-whites were often victimised. In 1884, amid growing tensions the company relocated the Chinese quarter outside City limits. The Chinese residents cleared the forest, levelled the site, and erected the buildings themselves, at no cost to the company.

The second Chinatown was a self-contained and self-supporting community, with its own merchants, doctors and entertainers. Because the increasing government head tax discouraged family members from entering the country, the community was predominately male.

In 1908, Mah Bing Kee and Ching Chung Yung bought 43 acres of company land, which included the second Chinatown site. To offset the cost of the purchase, they raised rents. In response, the residents formed the Lun Yick Company (Together We Prosper) and with the help of 4000 shareholders from across Canada purchased 9 acres of land from the coal company near the intersection of Pine and Hecate Streets. The residents then moved the entire community and its buildings to the new location.

The Third Chinatown (1908 - 1960)Edit

"He walked uphill a mile or so, crossed the railway tracks and continued until he came to Pine Street. A makeshift fence stretched across the street, and in front of a gate was a city sign: 'No Thoroughfare' . . . Pavement turned to dirt, and as he crested the hill, Chinatown lay before him. Pine Street ran another two hundred or so feet before it ended in a dead end at the edge of the bluff. The street looked like the set of a western movie. It was lined on either side with unpainted one- and two-story wood-frame buildings, some with false fronts, all with overhanging balconies that sagged and careened. The entire scene was bleached by the sun."

Excerpt from Denise Chong's, The Concubine's Children

By 1911, Nanaimo’s third Chinatown was well established, with buildings on both sides of Pine Street. The community had a population of approximately 1,500 which would swell on weekends when Chinese workers came from surrounding areas to socialize and purchase supplies. The City’s non-Chinese population also frequented Chinatown for commercial and entertainment purposes.

The population and economic vitality of the Pine Street Chinatown waned in the early 1920s due to a decline in the coal industry and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923. The area became increasingly derelict until it was destroyed by fire on September 30th, 1960. By this time the majority of the population had dispersed throughout Nanaimo or relocated to larger Chinese communities in Canada and the United States.

"Chinatown was considered a 'ghetto' in the small town. We were put in one place, and we didn't come out of that place because that's where we were supposed to stay. . . . we learned to stay within our own little Chinatown area. We lived on one street with Chinese people all around us."

Excerpt from Jin Guo (Jean Lumb - reflecting on growing up in the Third Chinatown)

The Fourth Chinatown (circa 1920s)Edit

During the 1920s, an extension to the third Chinatown known as “lower” Chinatown or “new town” developed on nearby Machleary Street. This extension was significant in that land ownership was no longer tied to a lease arrangement with the coal company or land bought collectively.

The LegacyEdit

Nanaimo’s Chinese settlers had a unique impact on the City’s history. Like all pioneers, they struggled against many obstacles and ultimately had to fight for recognition as Canadian citizens. After World War II, the removal of discriminatory immigration policy and acceptance of official multiculturalism allowed people of Chinese descent to take their place at all levels of Canadian society.

“When I went to school, I wished I wasn’t Chinese. There was lots of name calling and discrimination. If I wasn’t Chinese, I wouldn’t have to face this. I wanted to get out of Chinatown. Everything was old, the buildings were firetraps . . . you couldn’t really improve it. The young generation didn’t want to live there. Once they saved some money, they wanted to get out and live like everyone else in the community. It was much better after World War II . . . since we’ve been allowed to vote. You felt really great. Over the years, when I was operating my own business, I got lots of support from the whole community.”

Chuck Wong, on growing up in the Third Chinatown

“I was always proud of my heritage. I felt I was as good as anyone. After grade 4 or 5, I was pretty well accepted by the white students as their equal. There was discrimination and bullying but I had to stand up against them otherwise you’d always be picked on. When World War II started, enlisting was something that had to be done. I joined the RCAF even before we were allowed to vote. Our family never lived in Chinatown. For those that resided there, they felt more secure amongst themselves. After 1947 when we got the vote, if you had the ability or desire, you could be anything you wanted. After 1947 all the official barriers were gone.”

Dick Mah, on growing up in Nanaimo